A Creekside Walk at Taylorstown

A Picturesque Waterway, Loudoun’s Oldest Homes, An Old Mill,

and a Creekside Vineyard Make for a Pleasant Stroll at Taylorstown

Story by Richard T. Gillespie

Photos by Douglas Graham

In Northern Loudoun along Catoctin Creek, Native Americans settled early on leaving us a wealth of archaeological remains. Today, Loudoun’s two oldest homes, both of Quaker stone, sit on opposite sides of that same creek, along with our oldest extant mill dating to 1798. On the east side of the creek is Taylorstown settled by Quakers, on the west is Hoysville, settled by Germans from the Palatine region of west-of-the-Rhine Germany. In the 1970s, the creek was to be damned for a 3,800 acre reservoir to serve Washington but determined efforts by preservationists gave us today’s Taylorstown Historic District, a gurgling stream, restored old buildings, and a handsome creekside winery instead. This easy walk on a well-kept dirt road with lovely views along the creek connects the walker from Taylorstown to Catoctin Mills then reverses direction.

Directions:

From Leesburg: Take Route 15 north from Leesburg to New Valley Church Road (663) on the left, opposite the Little Rock Motel just south of Lucketts. Several miles out this will become Taylorstown Road, heading over the Catoctin Mountains down into the village of Taylorstown. Just pass the no-longer-open Taylorstown Store you will go down hill to a bridge across Catoctin Creek. Park on the left at the end of the bridge near the silver and black Virginia Department of Historic Resources sign entitled “Taylorstown”. Parking is on private property owned by David Nelson, owner of the Taylorstown Mill. Please be respectful of this privilege.

From Purcellville: From Route 7 head north on Route 287 past route 9 to Lovettsville. At the 7-11 there is a stop sign; turn right. Go through the small town of Lovettsville on Broadway, looking for the left, Lovettsville Road (672), immediately past the community center. Take this 3 miles to Taylorstown Road (668) on the right. At two miles on Taylorstown Road you will come to a bridge over Catoctin Creek. There is parking on the right just before the bridge. The parking is privately owned by David Nelson, owner and resident of the historic clapboard and stone Taylorstown Mill just across the creek. Please be respectful of this special privilege!

The Walk:

1. To begin the walk, cross the bridge over Catoctin Creek on Taylorstown Road and walk up the hill to Anna’s lane on the left. There you will see a cluster of buildings. You are at what is still called “Taylorstown.” The store on the left was built in 1935 to replace a store that had recently burned, this general store served residents until April 1998. It is hoped it will reopen at some date.

2. At Anna’s Lane and Taylorstown Road, look to your left. Set back from the road, “Hunting Hill” was built by Richard Brown, a recent Quaker arrival from Pennsylvania who constructed this classic stone Loudoun home in 1737. Its “cat slide” roof was common in Virginia before the American Revolution and there once were multiple examples around. But this one has survived to become Loudoun’s oldest building. Notice how understated it is! For many years in the mid-20th century it was the home of “Miss Anna” Hedrick, Virginia’s first female attorney. Builder Richard Brown went on to construct a mill across the road along the creek.

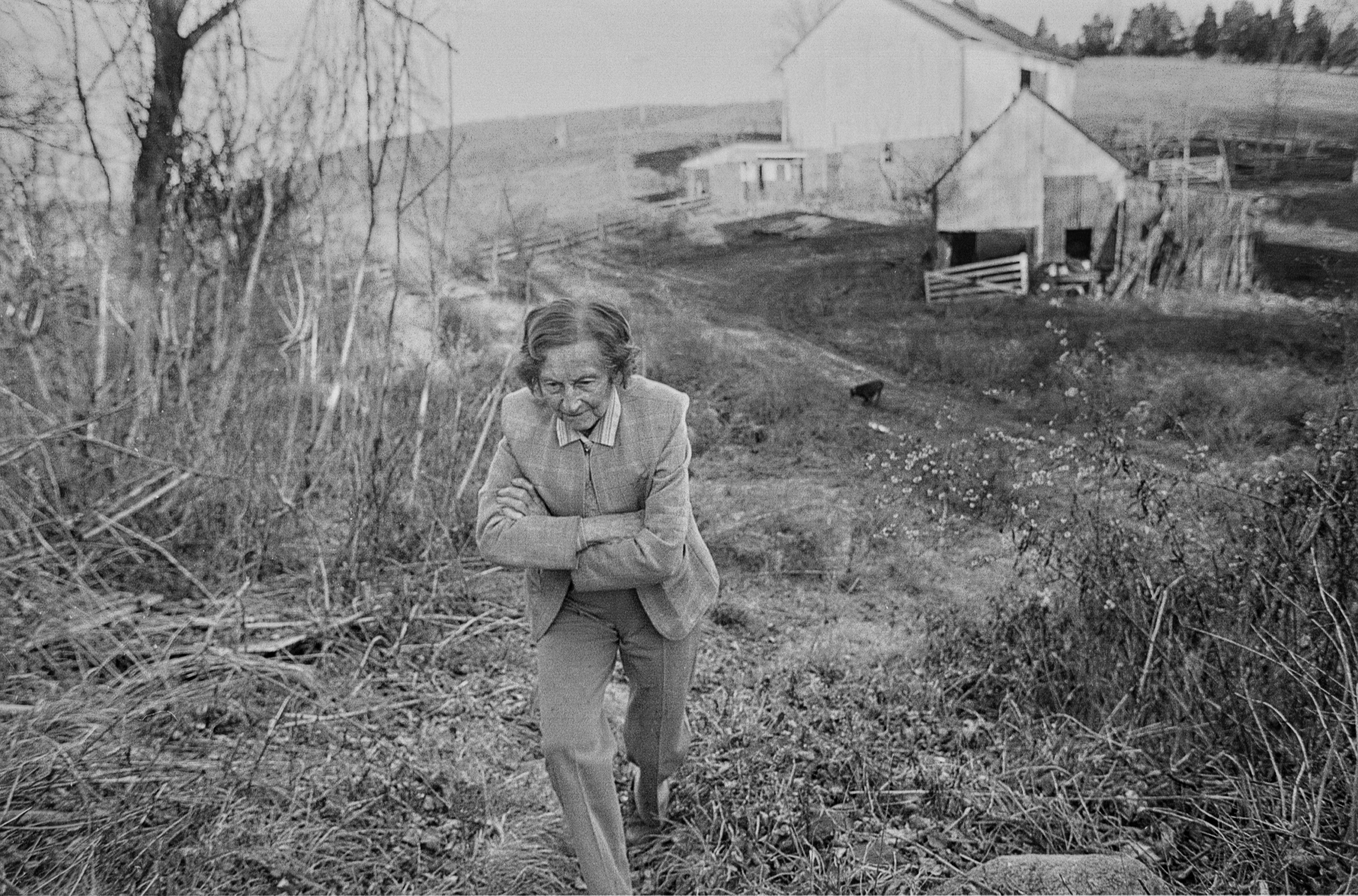

Anna Fancher Hedrick, also known as Miss Anna was a noted Loudoun County lawyer, equestrienne, and the first female judge in Virginia. Seen here in these photos from 1989 giving a tour of her beloved Hunting Hill in Taylorstown. (Archive photos by Douglas Graham)

3. Turn right back down the hill toward the bridge over Catoctin Creek. The stone building on your left is the Taylorstown Mill, which has gone by many names over the years. This stone and clapboard building was not the first built, but was an updated rebuild by Henry Taylor, who had inherited his father’s mill in 1797.

Incorporating a fully mechanized “Oliver Evans system,” this mill reopened in 1800. The new 1854 Furnace Mountain Road connected the mill directly to the new bridge over to Point of Rocks, Maryland, and with it, both the C & O Canal and the B & O Railroad to ship his grain. The Civil War-era owner, Henry S. “Stout” Williams, was a slave-owning secessionist and, to his woe, saw the Point-of-Rocks bridge blown up as a military necessity in June of 1861, cutting him off from his key markets. Worse, he was immediately arrested when Union troops finally crossed into Loudoun in the first week of March 1862. They confiscated his grain, his horses, wagons, and even his safe. Later, under duress, he swore allegiance to the Union and was allowed to return to his mill. Mills were seen as crucial to both sides’ war effort, producing both flour and feed for horses. Henry Williams’ “allegiance” likely saved his mill from later burning by federal troops as it did the Waterford and Aldie Mills, all still standing. The Taylorstown mill stopped grinding in 1932 but sold seed for another quarter century until 1958. The mill was later converted it into a residence. It is currently a private dwelling owned by David Nelson, who intensely cares about the history of Taylorstown and believes in historic preservation! The mill is private property; please be respectful.

4. Start back across the bridge staying on the left side. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a mill dam crossing the creek here which created a mill pond to feed into the mill’s headrace to power the machinery. You could walk atop the dam which many did since there was no bridge, but several drownings were the result. The dam virtually washed away on May 31, 1889, in the so-called Johnstown Flood. A bridge came in 1908—you still see the old abutments—and that was replaced by the current modern bridge in 1970.

5. Carefully go cross the Catoctin Creek Bridge to the right side so you can look downstream. While a lovely view, it may be the stone house across the creek—Foxton Cottage—that most catches your eye.

This house, again with a “cat slide” roof, was built very shortly after Hunting Hill, and along with the mill, is a key piece of the Taylorstown Historic District created in the 1970s. Again, notice the stone architecture imported from Pennsylvania.

6. Look for Downey Mill Road (663) on the left once you’ve crossed the creek. You’ll see a silver and black Virginia Department of Historic Resources “Taylorstown” sign at the intersection, which is worth the time to read.

7. Heading west on Downey Mill Road, you’ll be on one of the many “all-weather surface” VDOT roads, a.k.a., a maintained, graded dirt road. Loudoun has retained the largest number of these mileage-wise in Virginia, allowing a step back in time.

Newcomers sometimes find them a nuisance, but they are a part of the “vibe” in Western Loudoun and people drive them without a thought. There is always a fight when paving is discussed. Following the creek for a mile, this road floods out from time to time, but is generally fixed promptly as people rely on it to access their homes. As its name suggests, the road heads to Downey Mill, our destination, also sometimes called Hamilton’s Mills or Catoctin Mills. While the mill is gone, the tiny historic Virginia milling village remains.

8. You’ll notice almost immediately Hoysville Road on your right; this is the old road heading into the German settled area northwest of Taylorstown. Old houses here, whatever their modern cladding, are invariably log beneath the surface. These were largely Lutheran settlers arriving in the mid-18th century in a second wave of German settlement in Loudoun before the Revolution.

Patriotic in the American Revolution—many of them fought in Washington’s Army, especially Daniel Morgan’s Riflemen—they were not so interested in fighting for the Confederacy come 1861. However, many joined the Independent Loudoun Rangers, a Unionist cavalry unit formed by Waterford miller Samuel Means in the second summer of the war, 1862, that assisted the Union Army in the region. Means had been forced to evacuate his home for Maryland.

9. On your left you’ll begin to see a maze of stone walls—surely the remains of an historic building! Was it a mill?

No, and certainly not Catoctin Mill, which we’re heading to in three-quarters of a mile. In 1945, Loudoun builder Claude Honicon built this as a catch basin for gravel dredged from the creek, later to be used for construction projects in booming Northern Virginia. The New Deal and especially the Second World War led to massive home, shopping center, and road building. Today the simple stone walls leave most everyone intrigued, and it may be just as well; most don’t really know what an unexciting thing it was! It is private property and off limits, unfortunately. Still, from the road, it is beautiful to look at in late March and April when the interior is filled with wildflowers!

10. Shortly beyond these intriguing stone walls is a beautiful stretch of Catoctin Creek riffling over ledges and sandbars, with cattle often grazing in the green fields across the creek. It is photogenic and calming—a nice place to stop.

There are several good places to admire the view, even a ledge to sit on in the creek. (Please be careful!_ It’s fun to use your smartphone here to videotape the creek with the sound on for a later soothing playback. Try it!

11. Continue walking along the creek enjoying wildlife, flowers, and the two interesting houses you’ll encounter, built to sit above the flooding creek.

12. At 0.4 miles along Downey Mill Road, shortly before a small bridge, you’ll see the creek begin to make a sharp turn left (east), creating a handsome set of riffles.

Look across the creek at the turn and you’ll see what is known locally as “Taylorstown Beach”—a short stretch of creek with a sandy shore known for its early spring bluebells, for being a 1960s late-night teen hangout, and as a place where many a local having found religion were baptized through the years with permission from the owner. It is private and heavily posted “No Trespassing,” so please admire it only from the road, whatever your impulses. A large house can be seen above it at certain times of the year. Along with the arboretum created about it, this handsome modern stone country home was the home of the Vice-President of AOL—America Online, one of the early email giants that played a big role in eastern Loudoun’s hi-tech growth.

13. Just before Downey Mill Road begins to rise at 0.45 miles from the main road, a “run” flows under a small wooden bridge to flow out to Catoctin Creek.

It’s another pleasant place to stop, look, listen, and contemplate. Again, we recommend audiotaping the gurgling riffles.

14. Downey Mill Road now heads uphill and makes a 90-degree right turn, becoming quite high above the creek. It’s a beautiful place to walk, with no houses to interrupt the view and waterfowl frequently calling out as they fly along the creek.

However, vehicles use this road so please keep to the proper side and stay alert, especially at the sharp curve. Recently, a school bus and a car going in opposite directions clashed here. It was a bit of a conundrum. It took some “getting out of vehicles” to discuss and come to a resolution. “Life in the country,” as they say. It appears that the children all got out of the bus and walked home.

15. At 0.7 miles along Downey Mill Road, you’ll come to the complex once known as Hamilton’s Mills—later as Catoctin Mill, owned by one James Downey. Mr. John Hamilton of Hedgeland (still standing near Waterford) built this complex of buildings early in the 19th century. He even sold Hedgeland to finance the deal, which leads you to wonder if he realized an opportunity when he opened his “Hamilton Mills” in 1807, despite the mill a mile down the road at Taylorstown. That same year, Charles Fenton Mercer began Aldie Mill on Little River. It was the year Congress and President Jefferson imposed an embargo against the French and British during the Napoleonic Wars; they’d both been stopping American ships, seizing contraband cargos and impressing our sailors into their navies, coming up short as they were on manpower. We needed home production, and it was obvious that with foreign trade now largely cut off, the Atlantic coast trade would boom. Loudoun was known for its wheat and other grains; these visionaries wanted to use the new “Oliver Evans system” of mechanized milling to produce grain in large quantities while the trade to other states began to boom. It’s worth remembering that, in 1807, the Midwest was western New York, western Pennsylvania, and Ohio. The Erie Canal had not yet been built. Midwest agricultural competition would largely come is subsequent decades. So at that time, fertile eastern valleys like the Loudoun and Catoctin Valleys as well as the Shenandoah Valley were America’s breadbaskets.

Hamilton’s mills consisted of a merchant mill and a sawmill. A ‘merchant’ mill bought your grain, ground it, and shipped it in barrels to major cities and distribution points. You could also buy grain here. The mill here used a double overshot set of millwheels like the Aldie Mill, with “three run of burrs”—three sets of grind-stones—and all its machinery mechanized by that water power. There was also a water-powered saw mill on site. As with the Taylorstown Mill, a millrace upstream—the headrace—brought water from the creek to the mills; a tailrace brought it back. By the eve of the Civil War, industrious Washington County, Maryland, native James Downey owned the mill, and had an additional 30-horsepower stationary steam engine to help along the many milling activities. He also was running a steam distillery capable of converting 200 bushels of grain a day into mash and then whiskey. Rye was the preferred grain and the tasty whiskey of choice here in Virginia and Maryland. Hamilton’s Mills—later Downey’s or Catoctin—was three stories and stone, and looked much like the mill at Waterford. We have no pictures of the distillery or its popular stillhouse. The mill survived the Civil War, but burned in 1902. You’ll see a picture of the mill on the sign at the current day garage along the road. But where was the mill before it was destroyed? Across the road from the current stone garage on the hairpin turn, set back from the current board fence. It’s amazing how time changes a landscape!

16. The handsome elongated Downey House contained in the hairpin turn was built in stages over the years across from the mill by the mill owner. When the Hamiltons owned the mill, there was a even a post office here. Come the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, mill owner James Downey was a decided Unionist and rejected Virginia’s secession.

The federal government encouraged Unionists that summer to begin a break-away; this ultimately resulted in the creation of a rump Unionist government that met at Union-occupied Alexandria (taken the day after Virginia seceded in May 1861). Downey was elected to thelegislature, and in 1863-64, was elected Speaker of the House of Delegates there. Downey was arrested and jailed three times in Loudoun by the Confederate authorities, and eventually had to live across the river in Maryland when not attending the government sessions. His daughter Lilly had to run the mill then until she died of consumption in January 1865. It is said that Mrs. Downey, who had helped her daughter run the mill, had to pay off the famed Gray Ghost John Singleton Mosby to keep her husband from being killed. The Downeys lost their son, John, in 1862 when he was acting as a civilian guide for federal forces, killed near Salem in Fauquier County. Their daughter Susan Alice married the drillmaster of the Unionist Loudoun Rangers, Sergeant Charlie Webster, and they lived here at the house in the early days of the unit, created during the summer of 1862. But Charlie was captured in fighting with local Confederate cavalry at nearby New Valley Church (you likely passed it driving in) on September 2nd, and ultimately was tried and convicted in Richmond for the murder of Loudouner James Simpson, captain of a company of the 8th Virginia Volunteer Infantry (Confederate) while home at North Fork on recruiting duty in January. Charlie was sentenced to hang; he jumped from the third story of his prison the night before. With both legs broken, he was hanged while sitting in a chair that cold 1863 day. His young wife died just four months later of consumption. And Unionist Virginia? Loudoun never got to join—we didn’t even get to vote—but it was created during the Civil War in June 1863—West Virginia, where Virginia’s Unionists were concentrated. Still, the Unionist rump Alexandria government continued to exist until 1865.

17. As you make the corner beyond the garage starting to turn back on yourself, on your left you will see some walls and bits and pieces of buildings. Somewhere within this stood Downey’s Whiskey Distillery—or in

local parlance, “Downey’s Still House.” It was destroyed in 1865, a pity, but there’s a story here. It seems the stillhouse was a popular “meeting” place by operators from both sides during the Civil War—Mosby’s men, the Loudoun Rangers, even the “Commanches,” members of the local Confederate 35th Virginia Cavalry. Over a dram of Virginia’s best, one could learn of all sorts of wartime goings on that could prove useful intelligence. Unfortunately for the Downey’s, they were using grain for “drankin’” that could have been more usefully employed to feed the Confederate army and its livestock defending the Virginia homeland against the federal invaders.

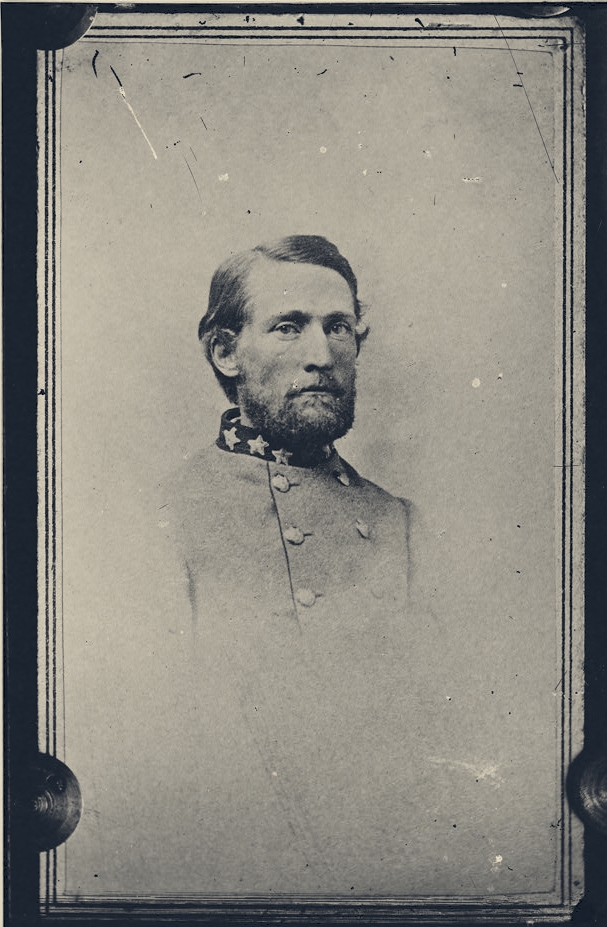

Above: Colonel John S. Mosby.

Colonel John Singleton Mosby—chief of the 43rd Virginia cavalry, Mosby’s Rangers, based in southwestern Loudoun and Upper Fauquier, did not cotton to this. On March 26, 1865, an indelibly sad Sunday, the Rangers arrived to destroy the Downey’s still. It is said that they poured the contents into nearby Catoctin Creek before destroying the stills and the stillhouse. One wonders if they “paused to refresh” before completing their difficult duty? The following Thursday, March 30th, Mosby’s quartermaster “Major” Hibbs with two other Rangers returned to exact a “tithe” of bacon on the Downeys to help feed Mosby’s many companies of Rangers. Mrs. Downey kept them talking as she went about complying with their demand—occupied enough that they did not see the Loudoun Rangers creeping up to the Downey place. The three were captured, infuriating Mosby, who virtually destroyed the Loudoun Rangers over in Jefferson County during a large raid a week later at Key’s Switch near Harpers Ferry. Ironically, Lee’s surrender at Appomattox was just a few days away. Partisan warfare was particularly bitter and grueling during the “late unpleasantness” here in Loudoun. It would be long remembered. By the by, the current owner of the mill complex, a fine steward of the historic property, maintains that when the light or the fog is just right, he has several times encountered the apparition of a Civil War soldier on the curve as he walks past the mill and distillery sites. Is it Charlie Webster come home from his hanging only to find that after all he’d been through, his beloved 21-year-old wife Susan had also passed on with the consumption? One can wonder. The current owner begs to be allowed his privacy; please be respectful of that.

18. Starting up the hill on the far side of the hairpin, you will see the restored miller’s house on the left—the mill owner and the miller were almost always separate people in the operations of larger “merchant mills.” It is a classic piece of this region’s architecture. At one time, a small store was also here.

19. Don’t exhaust yourself going up that long hill; there’s really no view! Rather, simply turn ‘round, and have a leisurely walk back along the creek. A glass of wine is waiting for you at Creek’s Edge Winery. Interesting how the creek looks different walking the other way!

Post-walk refreshment: As with pub walks in Britain, America’s Routes likes to give you a post-walk recommendation.

–Creek’s Edge Winery obviously provides Virginia wine, food, and a great view and we commend it to you. You can take your wine or food down to the picnic tables, some of which are right along Catoctin Creek.

There’s often music on weekends. At your car by the bridge, cross over the creek, go up the hill, and turn left onto Anna’s Lane. It’s at the end.

-If you’ve had your thirst whetted by our stories herein about whiskey—or perhaps you had wine before you went on the walk—consider turning left onto Taylorstown Road when leaving. At a little under two miles on the right is Flying Ace Brewery & Distillery, shortly before you reach Lovettsville Road. At Flying Ace, heirloom (and appropriately named) Bloody Butcher corn is grown right at the farm and is being made into moonshine and subsequently bourbon. They also brew their own beer. The complex makes use of the old Simpson Farm, a nice piece of indigenous architecture.

_______________________

Curated and written by Richard T. Gillespie, Historian Emeritus of the Virginia Piedmont Heritage Area and local Taylorstown resident. Warm thanks go to historian and mapmaker Eugene Scheel for his massive research into the neighborhood, to Clare Metheny for her research on the Taylorstown Mill, to Craig Trout for researching Downey Mill, and to Roland Osbourne formerly of Taylorstown for his earlier version of this tour.

The Lincoln Loop

A Rural Road Tour in the Heart of Western Loudoun

By Richard T. Gillespie, Historian Emeritus, Mosby Heritage Area Association Photos by Douglas Graham

The historic Lincoln area, once known as Goose Creek, has some of the most handsome Quaker architecture in Loudoun County. This three-mile loop walk travels the rolling country of well-tended, carefully-sited farms, rural roads, and classic stone and brick Quaker homes. This walk also includes the likely site of a Civil War skirmish and two Friends’ meetinghouses. One modern 21st century intrusion you will come upon as a surprise. This is the heart of western Loudoun, and yet just two miles from increasingly urban Purcellville. This tour can be done on foot, horseback, bicycle or by car.

Directions:

From Leesburg: Take Route 7 West to the Purcellville/Route 287 exit. Turn left at the end-of-exit light onto Route 287. Follow this through two stoplights to a roundabout, go 180º around it and continue south. At the next stop sign, turn left onto Route 722, Lincoln Road. A mile south, you will come to the village of Lincoln, introduced by a sign on the right and an elementary school on the left. Look for tiny Cookesville Road on the right, and immediately after, the small dirt parking lot by the graveyard for the Goose Creek Friends (Quaker) Meetinghouse, which is across the street. Park here to begin your walk.

The Tour:

STOP ONE: The Goose Creek Friends Meeting graveyard immediately borders the parking lot. It is still in use. The simplicity of Quaker stones, some dating back more than two centuries, tells you much about the ethic of the Friends, as they called themselves, despite their education, middle class, and economic wealth.

STOP TWO: As you leave the parking lot, you will notice an ancient stone house with dark brown trim on your right. This is the earlier Quaker Meeting House of Lincoln – Goose Creek Friends Meeting. There is a plaque on the building that reads:

“This Stone House served as the place of worship for Goose Creek Friends from 1765 to 1819. It has served as the residence for the caretaker of the meeting’s property since that time.”

The current single-story Friends Meeting House is across the street, dating to 1817-19. This newer meetinghouse originally had two stories, but lost one in a 1943 storm. There are benches in front of the Meeting; feel welcome to sit there and orient yourself to this walk before embarking. Look in the windows—simple pews, no religious symbols, no altar. You can come to a service any Sunday at 9:45 a.m. The Quakers, their meetinghouse, and their Goose Creek neighborhood are the keys to this walk.

The Religious Society of Friends – “Quakers” – arrived in Loudoun County from Quaker-settled Pennsylvania in 1733, finding that colony becoming crowded with good land in short supply. The Loudoun Valley’s fine soil fit the bill. Initially, Quakers settled some seven miles to the north in and around the village of Waterford, but soon spread out. The Goose Creek Friends Meeting followed in the 1740s.

Quakers, a Christian sect founded in Lancashire in England in the 1650s as an outgrowth of the Puritan movement, believed in the “Divine Spark” in every human being, regardless of race, nationality, or gender. It was their consequent duty, they felt, to learn to read the Bible to bring out that spark, and they worked to promote education, treat all fairly and as equals (including native Americans), eschew slavery, and to worship without fancy churches, symbols, or idolatry, and avoid violence or war. Those who so pledged and became part of a Quaker congregation were held to these standards or forced out of the meeting.

Well-educated and middle class for the time, they brought superior methods of farming and trade to Loudoun with a good sense of how to preserve the land as a resource. In time, Loudoun’s Quakers established Fairfax (Waterford), Goose Creek (Lincoln), The Gap (Hillsboro), and South Fork (Unison) Meetings. Only Goose Creek Friends Meeting survives today, meeting weekly.

Those attending note the lack of crucifixes, statues, fancy artwork, and particularly, a minister, preacher, or priest. Friends meditate at meeting, then stand and share when the spirit moves them. Today’s Meeting is a mix of descendants from early families and people who have moved more recently to Loudoun County.

STOP THREE: To explore a part of the Quaker realm here in Loudoun, cross the lawn from the modern meetinghouse to the small brick building just across Sands Road. This is the circa 1815 one-room Oakdale School. One of the earliest schools in Loudoun and today its oldest, this early 19th century Quaker school could be attended for $15 per year (about $1200 in current dollars) in the times before Virginia had public schools. The school was open year ’round, except for harvest time.

Today, it is still used for day care, Sunday school, and a living history one-room school program. It is the embodiment of the Quaker ethic: All could attend for a modest cost-basis fee since education is key to the development of the Divine Spark in every human being. A plaque on the building says:

“Oakdale School house was built in 1815. It served as a Quaker school until 1885, a few years after the opening of the Public Schools.”

STOP FOUR: Continue to the back of the school to a second gravel road, joining Sands Road in a “V”. This is Foundry Road, which you will be taking. Just beyond Oakdale School on the left is a fine house-like brick building that was the first public school in Lincoln. It was originally the Lincoln Graded School from 1880 to 1909, and subsequently the Lincoln Elementary until 1955. Catherine Marshall, author of the acclaimed novel Christy, about a young woman teaching in Appalachian Tennessee, was a recent resident. Today, it continues as a private dwelling, but emphasizes again how the importance of education was stressed in this area of Loudoun. Virginia was, after all, the last state in the Union to adopt public school, forced to by the federal government after the Civil War.

STOP FIVE: Continuing to 0.2 mile along Foundry Road, a fine grove of pines appears on the left, not particularly common in these parts. This is the beginning of Somerset Farm, built about 1820, whose handsome yellow pargeted (painting on white plaster fresco-style) walls and red tin roof soon appear behind the board fence.

You will get several views of this estate-like farm; at 0.5 miles on a curve in the road, you will have a fine prospect over the farm’s pond of the front of the main house. Note two things: the house is nicely nestled on its hillside for economy of heating and cooling (not put garishly on a hilltop for all to see as today) and it is a fine home. Quakers, industrious and avoiding show, were prosperous.

The road now heads downhill. Looking to the right across the horse fences, you will see another classic Quaker farmhouse in the distance. Notice how it is sited – nestled – the Quaker ethic again at work.

STOP SIX: At the base of the hill, the terrain opens into a park-like setting in the bottomland created by Crooked Run, and then crosses a small bridge. Immediately beyond the small bridge, on the right-hand side of the road, sat Taylor’s Foundry, from which the road gets its name. Richard Henry Taylor made plows and bells here in the late 1860s and 1870s, quite necessary in this farm country.

Just beyond on a small hill also on the right is a new home built in the Loudoun vernacular style, a pleasant blending with its environs. Note the horse jumps just beyond the driveway. Loudoun is a paradise for horse owners.

STOP SEVEN: At 0.9 miles on the left, just before an intersection, sits a very old stone Quaker cottage (circa 1749) that once belonged to Jacob and Hannah Janney, two of the earliest Quaker settlers. Raising twelve children here, Hannah was one of the leading lights of the congregation, praying near a fallen log as her natural alter until the first meetinghouse was built in 1765.

Quakers had brought their Lancashire stone architecture from the English midlands to Pennsylvania, and thence to Maryland and northwestern Virginia. Note the springhouse just a little farther along. The home has been lovingly restored by Virginia poet and educator Perry Epes and his wife Gail. He wrote, “We bought this farm to live again.” Extensive preservation efforts by groups and individuals like the Epes are one of the reasons that Loudoun is part of two heritage areas celebrating historic preservation – the five-county Mosby Heritage Area and four-state Journey Through Hallowed Ground.

STOP EIGHT: At 0.95 miles, just beyond the Hannah Janney cottage, turn left onto Rt. 726 (Taylor Road). Note the steep banks as you enter the road – it is indicative of how long vehicles have been cutting the road deeper, and thus just how old this road is. This is something commonly seen in Loudoun throughout its historic rural routes network. A short distance down the road is a bridge over one of the meandering branches of Crooked Run. It is a nice place to dawdle.

STOP NINE: Moving along Taylor Road you will almost immediately come to a stone and weatherboard barn on the left as the road curves. Federal troops came to the Loudoun Valley to burn barns, corncribs, crops harvested in the fields, and mills while confiscating all livestock in November 28 – December 2, 1864 as a way to starve out the Confederacy and particularly the Mosby Ranger guerrilla operation based just south of Lincoln. The whole region of this walk was burned over. A boy out shooting small game hid in this barn when the troops came; evidently his rifle was enough to guide federals away from this old structure. And so it stands, photogenic and symbolic.

STOP TEN: Opposite it is a tree-lined lane that leads into Coolbrook Farm, where Pulitzer Prize-winning Virginia Poet Laureate Henry Taylor grew up. The brick farmhouse was built in 1827, and suffered through the burning raid. Notice the stone outbuildings and barns. This farm, these fields, this babbling Crooked Run was inspiration for much of his poetry. In his poem Harvest Taylor wrote, Every year in late July I come back to where I was raised/ to mosey and browse through old farm buildings/ over fields that seem never to change . . .

STOP ELEVEN: From here the dirt road heads uphill. At the crest, there is a gate on the left offering a beautiful panorama to the west over rolling, hilly pastureland. Opposite, is a view east over open country looking toward Hogback Mountain, part of the eastern most foothills of the Blue Ridge.

From these overlooks, the world seemed afire during the 1864 burning raid. How ironic that the Quakers were among those so targeted. Homes like Coolbrook Farm were saved by the efforts of desperate Quaker lasses on bent knees. While the Union boys did not target homes, barns burning often set houses alight.

STOP TWELVE: At 1.4 miles, nearing the halfway point of the walk, you will see a classic Victorian vernacular white clapboard farmhouse on the left. This is Ferris Hill Farm (circa 1877), home of the late Judge Julia Cannon, a descendant of one of Loudoun’s first Quaker families. Just beyond, under the huge spreading limbs of an old oak on the same side of the road nearing a slight crest in the road, there is a fine view over the horse jumps.

You can see the Blue Ridge rising to the west, and to the northwest is the water tower indicating the location of Purcellville. It’s a fine place to catch a sunset.

STOP THIRTEEN: At 1.65 miles, at the crest of another hill, there is a handsome brick Greek revival farmhouse on the right, with two barns across the road. Bonnie Mersinger Carroll grew up here. Carroll won the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 for founding Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS) in 1994 after her husband, a general officer, was killed with seven others in a military plane crash in Alaska. She works with the families of those lost in the military. As a girl and young woman, she walked these same roads, often riding her horse. She is an accomplished equestrienne, though no longer lives here.

STOP FOURTEEN: Just beyond, coming up a slight rise, is a surprise – much fought over on this historic Quaker landscape, to be sure. A local doctor left land to the local non-profit hospital; they sold it to finance a new suburban campus well east of the center of the county. You will view the result.

STOP FIFTEEN: Taylor Road ends at historic and recently paved Sands Road (Rt. 709) at 1.95 miles. The paving of this ancient roadway was controversial, unneeded over more than two centuries until . . . Well, you can guess. Now this winding Quaker lane has been suburbanized.

However, in a short distance, it returns to its historic ambiance. Across the intersection, you will see a fine stone Quaker farmhouse and stone and white weatherboard barn surrounded by new houses. The Brown farm, belonging to an old Loudoun family, sold off most of its acreage in the mid 1990s when farming no longer prospered sufficiently on the site. Certainly this is a picture often repeated in recent years. However, another long-time Loudoun family uses the smaller farm, and is heavily involved in history and historic preservation. They raise sheep, and insistently use the old roads to move their sheep between fields.

Heading left on Sands Road, you will head downhill to cross another branch of the ubiquitous Crooked Run. Look back over your right shoulder and you will see a picture of barn, silo, and farmhouse less spoiled by new development.

STOP SIXTEEN: Now head uphill. Near the top of the hill, beyond Manassas Gap Court on your left, you will see a tree line on the right and left sides of the road. This marks the railroad cut of the Loudoun Branch of the Manassas Gap Railroad. It was to connect Harpers Ferry to the Manassas Gap Railroad in the vicinity of Centreville, via Purcellville. This would require tunneling under Hogback Mountain to the east, which was begun in the years 1855-57. The Irish railroad workers ran into trouble with local Quaker maidens in 1857, necessitating the militia be called out. The officer in charge was Turner Ashby’s brother, Richard. In 1857, the financial panic of that year put an end to the Loudoun Branch plans for the time being, and then the Civil War came and the idea was never revived. It sits here as an aging relic of past dreams.

STOP SEVENTEEN: In the railroad cut to the left, John S. Mosby’s Confederate raiders of the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry gathered on Tuesday, March 21, 1865, less than three weeks before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Some of the Rangers had been sent to Purcellville where there was a large Union force (approx. 1500) under Colonel Reno, with the object of luring Union cavalry in pursuit. They succeeded, turned, raced for Hamilton, passed through the village (sometimes then called Harmony), and then turned down this Hamilton-Lincoln Road.

Six raiders under Charlie Wiltshire galloped up this road in the direction you’ve been walking, with Lt. John H. Black and Company G of the 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry in hot pursuit. Captain Glascock of Mosby’s command had 103 men here in the railroad cut waiting to attack the flank of the Federal cavalry as it passed and slowed for the curve just above.

Mosby arrived on the scene just before Wiltshire and the pursuing Federals, and wanted to move his men back further into the cut. (Look down this tree line on the left and you can still see the cut where Mosby’s men were hiding.) Lt. Black and his men saw Mosby’s men moving, and charged; Capt. Glascock ordered a countercharge. The raiders chased the Federal cavalry all the way back to Hamilton, unfortunately failing to stop short, thus running into a line of Federal infantry at what is now the edge of town. They suffered several unnecessary casualties including more than five wounded and two new recruits killed. However, the federals lost nine killed, 12 wounded, and 10 prisoners.

Lt. Black himself was so badly wounded that he was left to die in the road, made worse by the season’s first violent thunderstorm that broke during the action, coming in from the southwest. It happens that a Quaker widow and her daughters either saw the action from a distance or happened along after the soldiers had left the scene. They retrieved the young Lieutenant, placing him in their wagon, They hid him for several weeks at their home while nursing him back from the brink. Ultimately, he was returned to the federal base at Harpers Ferry. Because of the women’s courageous deed in a Confederate-dominated section of the county, the “gallant lieutenant” survived to go home, living another sixty years back in Pennsylvania as a limping yet inspirational English teacher.

Madison Cawein (1865-1914) commemorated this skirmish in his 1888 poem “Mosby at Hamilton“:

Down Loudoun lanes, with swinging reins

And clash of spur and saber,

And bugling of the battle horn,

Six score and eight we rode at morn,

Six score and eight of Southern born,

All tried in love and labor.

Full in the sun at Hamilton,

We met the South’s invaders;

Who, after fifteen hundred strong,

‘Mid blazing homes had marched along

All night with Northern shout and song

To crush the rebel raiders.

Down Loudoun lanes, with streaming manes,

We spurred in wild March weather;

And all along our war-scarred way

The graves of Southern heroes lay,

Our guide-posts to revenge that day,

As we rode grim together.

Old tales still tell some miracle

Of saints in holy writing–

But who shall say while hundreds fled

Before the few that Mosby led,

Unless the noblest of our dead

Charged with us then when fighting?

While Yankee cheers still stunned our ears

of troops at Harpers Ferry,

While Sheridan led on his Huns,

And Richmond rocked to roaring guns,

We felt the South still had some sons

She would not scorn to bury.

Raiders James Keith (17) and Wirt Binford (18) were two of those sons who fell that wild March day.

Recently, historians have wondered whether this action began here or back up the road closer to Hamilton a ways; still, the story stands wherever it occurred and may well fit this railroad cut location the best.

To this day, no one knows who the Quaker mother and her daughters were. They likely would have wanted it that way. The story of the heroism of these lady Quakers was discovered locally only in 1981 when Lt. Black’s letters were discovered and published in a West Virginia history magazine, keeping local historians debating ever since.

STOP EIGHTEEN: Just beyond the railroad cut, the road turns 90 degrees left beneath a massive spreading oak on the right corner. A quarter of a mile down the road, you will cross a creek – another branch of Crooked run, no doubt! In the best of country spirit, note the swing hanging over the creek from a tree limb on the left. A few yards past the creek, there is a fine prospect off to the right of a brick Quaker farmhouse set back from the road. Built about 1815, it has been lovingly restored by a descendent of one of the earliest Goose Creek Quaker settlers. They maintain that Lt. Black was not kept here…

STOP NINETEEN: You will climb a hill after the creek. At its crest, look through the gate on the left for another fine view of Hogback Mountain to the east. Just beyond, behind tall boxwoods on the right, is a Victorian vernacular house that once served as a store but now has been preserved as a residence.

STOP TWENTY: At 2.75 miles, the road heads downhill, and a view of open fields appears on the left as you begin to enter the village of Lincoln. At the base of this steep little hill, before the last rise into Lincoln on the right, sits a striking elongated white weatherboard farmhouse with a long front porch. It is set back from the right side of the road, but at the road itself sits a small bank barn. It has long been rumored to have been a temporary hiding place on the Underground Railroad. Several Quakers in this area were reputed to be quite active in helping slaves to freedom, but the proof of their careful operations has been nearly impossible to come by, leaving us with a delicious mystery. It may also speak to their success.

Now climb the hill to return to the village of Lincoln where you began. Hoping for a village post office once the Civil War was concluded, residents applied to Washington indicating their willingness to have the post office named for the recently assassinated President Lincoln. They got their post office, the first such to be so named in the South. The old name “Goose Creek” still remains as the name of the meetinghouse and of the Loudoun County Historic District you’ve been walking through. You may wish to return to that wide Meetinghouse porch at the top of the hill with its benches to pause for breath.

Your loop is now complete. Cross the street to your vehicle. You now have an idea through walking a sample of Loudoun’s historic roads network of the heritage of this Northern Virginia county. You’ve also seen some of its preservation victories, and one of its glaring failures. You have much to ponder!

Refreshment can be found at a number of places when you return on the road where you’re parked to Purcellville, two miles north. These include five microbreweries, a distillery, multiple wineries, coffee shops, and restaurants in shopping centers and in the historic downtown section at Main and 21st Streets.